This is the story of Adnan.

Adnan is not an actual person; his story is meant to illustrate what might have happened in the educational journey of a child born in Syria in 2003 who was forced to migrate to Turkey — what they would have learned in school, gaps in their education, changes they would have faced in the transition to the Turkish system, ways in which the Turkish system is similar and different to that of the Syrian system, and challenges that they faced and continue to face.

Born in 2003 in Aleppo, Syria

Adnan, Age 6

Adnan starts 1st grade at a public school near Aleppo. Syrian primary education starts at age six and is compulsory and free for all youth. Adnan’s curriculum is very similar to that of his peers; curriculum is established on a national level by the Syrian Ministry of Education. Teachers at all levels in the Syrian system are required to have completed a four-year bachelor’s degree in order to teach. 1

21 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 7

Adnan starts 2nd grade at the same school. His curriculum is similar to that of first grade.

21 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 8

Adnan starts 3rd grade at the same school. 2011 sees the start of uprisings against the regime of Bashar al- Assad. 2 Adnan’s life in Aleppo is largely unchanged, though there is talk of war.

Take a deeper dive

Losing family members, witnessing violence, or being forced to leave home can be very detrimental to learning

21 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 9

In July 2012, rebels captured half of Aleppo. In July, government forces bombed the city, forcing about a million people to evacuate, including Adnan and his family. 3 They fled to Turkey, which is about 40 miles (64 km) from his home. Adnan would have been in 4th grade, but the was forced to leave before the start of the school year.

0 hours of class/week

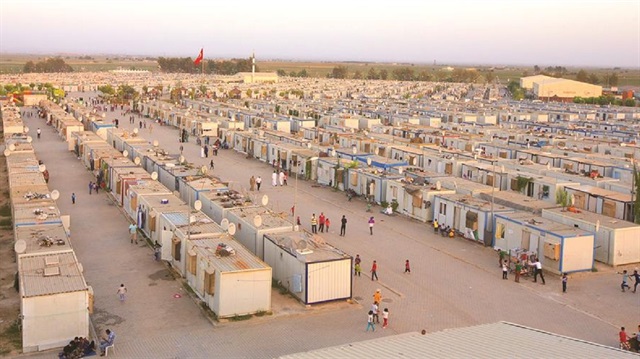

Adnan and his family, like many others, crossed the border near Kilis and were registered as refugees by the Turkish government. The Turkish government, starting in 2011, is working under a “temporary protection” framework, which means that Adnan and his family receive “temporary protection” status. 4 For the time being, he and his family stay at Öncüpinar Container City, located in Kilis Province and opened in March 2012. They live in one of 2,053 containers. 5 Due to circumstances beyond his control, Adnan misses 4th grade.

Adnan, Age 10

In April, the General Directorate for Migration Management is established by the Turkish government. Along with its establishment, the Turkish government reaffirms its commitment to education for refugees, stating that all refugees have a right to access education. 6 There is a Temporary Education Center in the Container City, but like many other Temporary Education Centers up until 2014, it is run by a private organization and charges a fee for attendance. Adnan’s family cannot afford to send him to school. 7

Take a deeper dive

When refugees and host countries view their status as temporary, education suffers.

0 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 11

By 2014, Adnan is able to start 4th grade at the Temporary Education Center in the camp. However, his family warns that they will have to leave soon; the camp is becoming crowded and his father wants to look for work in the city. In 2014, the Ministry of National Education issues a circular titled Educational Activities Targeting Foreigners,” which asserted the educational rights of foreigners and procedures for enrolling in public schools in Turkey. Part of the legal framework was specifically directed at Temporary Education Centers. Previously, many of the schools were outside of the control of the Turkish Ministry of Education, but the circular introduced new supervision and monitoring of the TECs by the Turkish government. 8

Education in Temporary Education Centers (TECs)

20 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 12

Adnan and his family move out of the container city to the nearby city of Gaziantep in southeastern Turkey. This move from camp to city is similar to many Syrian refugees in Turkey; by 2019, only 3.85% of 3,651,635 refugees are housed in camps. 12 Because Adnan arrived in Turkey in 2012, just after the Turkish government solidified its Temporary Protection framework, he was able to be registered. All Syrian children must have a Temporary Protection Beneficiary Identification Card in order to attend school, get a diploma, or graduate. 13 In Gaziantep, Adnan is registered to attend the Turkish lower secondary public school with other 5th graders.

Education in Public Schools 14

30 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 13

Before the start of the 2016-2017 school year, the Turkish Ministry of National Education announces a plan to integrate all Syrian children into Turkish public schools, phasing out Temporary Education Centers completely by 2020. That September, TECs were not accepting first, fifth, or ninth graders, forcing them to enroll in public schools. 17 7th grader Adnan was already at public schools, but he is one of few. By 2019 in Gaziantep, there will be major overcrowding issues and a need for new infrastructure. In Adnan's school of 1650 children, 742 (45%) are Syrian. 18

Take a deeper dive

The surging refugee student population strains existing facilities

30 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 14

Adnan starts 7th grade. By 2017, there are 425 Temporary Education Centers in Turkey. In 2018, this number will drop to 318. 19 The Turkish government is planning to shut many of them down; the EU’s Promoting Integration of Syrian Children into Turkish Education System project has contributed 300 million Euro for increasing quality of education and 200 million Euro for school construction. 20 Ultimately, they hope to integrate Syrian students into the Turkish public school system.

TEMPORARY EDUCATION CENTERS

30 hours of class/week

Adnan, Age 15

At 15, Adnan starts 8th grade, two years behind his classmates. In 8th grade, he is enrolled in “History of the Republic of Turkey and Atatürk’s Principles,” a course that he struggles with while his Turkish classmates are relatively prepared. 21

Take a deeper dive

Public schools, where the language of instruction is entirely in Turkish, add an extra layer of difficulty.

30 hours of class/week

Starting in 2016, 1st, 5th, and 9th graders were required to register at Turkish public schools. Undoubtedly, some students dropped out of school rather than register for the public school — this could be due, among other things, to language barriers, lack of viable transportation options to get to school, resistance on the part of the parents, or need for another source of income to make ends meet. In 2017, according to the most recent statistics, enrollment at public schools surpassed that of TECs for the first time since 2011. As the Turkish government closes camps and TECs, with 6 of 19 camps closed in 2017 as a result of austerity measures, the number of Syrian refugees in public schools will continue to grow.

Adnan, Age 16

Adnan starts high school at a public Turkish high school in Gaziantep. High school in Turkey is far more challenging than middle school – he is enrolled in 9 different classes and the hours in class per week increase from 30 to 40. Starting in 9th grade, high schoolers in Turkey begin preparing for the Student Selection and Placement System, also known as the Öğrenci Seçme ve Yerleştirme Sistemi (ÖSYS), which means that teachers are increasingly focused on testing and preparing their students for the exams. 22 23 Adnan is worried that he might have to repeat 9th grade, a common occurrence for his Syrian friends.

40 hours of class/week

CONCLUSION

Out of 3,644,342 total refugees registered in Turkey, 45.51% are ages 0-18 — 32% are school age, and another 14% are soon to be school age. 24

Adnan’s story is not representative of all Syrians in Turkey. However, the challenges that he has faced and the types of education he’s received are indicative of many Syrian children. By 2020, the Turkish Ministry of Education aims to shut down Temporary Education Centers completely, integrating all Syrian children into public schools. 25

An entire generation of Syrians stand to lose out on education due to the conflict and subsequent displacement. The total number of Syrian children out of school skyrocketed from 0.9 million (14%) in the 2011/12 school year to 2.8 million (40%) in the 2014/15 school year. 26

As of March 2018, 38.2% of Syrian children (350,000 students) in Turkey are not currently in school. 27

Currently, school drop-out rates among Syrian youth are extremely high. Even though Turkey legally guarantees education for all children, there are many obstacles that can often get in the way. Read more about some of the primary challenges:

SOURCES

- 1 Education in Syria, https://wenr.wes.org/2016/04/education-in-syria

- 2 Syria Timeline: Since the Uprising Against Assad, https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/02/syria-timeline-uprising-against-assad

- 3 Aleppo Conflict Timeline - 2012, https://www.thealeppoproject.com/aleppo-conflict-timeline-2012/

- 4 Temporary Protection in Turkey, https://help.unhcr.org/turkey/information-for-syrians/temporary-protection-in-turkey/

- 5 Turkey and Syrian Refugees: The Limits of Hospitality, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Turkey-and-Syrian-Refugees_The-Limits-of-Hospitality-2014.pdf

- 6 Evolution of national policy in Turkey on integration of Syrian children into the national education system, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266069

- 7 Access to Education in Turkey, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/access-education-1

- 8 Yabancılara Yönelık Eğitim - Öğretim Hizmetleri, http://mevzuat.meb.gov.tr/dosyalar/1715.pdf

- 9 Access to Education in Turkey, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/access-education-1

- 10 Göç ve Uyum Raporu, https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/komisyon/insanhaklari/docs/2018/goc_ve_uyum_raporu.pdf

- 11 Access to Education in Turkey, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/access-education-1

- 12 Göç İstatikleri, http://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik6/gecici-koruma_363_378_4713_icerik

- 13 Access to Education in Turkey, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/access-education-1

- 14 World Data on Education: Turkey, http://dmz-ibe2-vm.unesco.org/sites/default/files/Turkey.pdf

- 15 Turkish government allows headscarf for 5th graders, causing uproar, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-govt-allows-headscarf-for-fifth-graders-causing-uproar-72062

- 16 Elementary School Curriculum Reform in Turkey, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255657070_Elementary_school_curriculum_reform_in_Turkey

- 17 Evolution of national policy in Turkey on integration of Syrian children into the national education system, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266069

- 18 Syrian and Turkish children go to school together in Turkey’s southeast, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/syrian-and-turkish-children-go-to-school-together-in-turkeys-southeast-121796

- 19 Evolution of national policy in Turkey on integration of Syrian children into the national education system, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266069

- 20 Promoting Integration of Syrian Children into Turkish Education System, https://www.avrupa.info.tr/en/project/promoting-integration-syrian-children-turkish-education-system-7010

- 21 Basic Education in Turkey: Background Report, https://www.oecd.org/education/school/39642601.pdf

- 22 More than 2.2 million students to take university entrance exam, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/more-than-22-million-students-to-take-university-entrance-exam-in-turkey-110661

- 23 Turkey Country Guide, https://www.export.gov/article?id=Turkey-Education-Services

- 24 Göç İstatikleri, http://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik6/gecici-koruma_363_378_4713_icerik

- 25 Evolution of national policy in Turkey on integration of Syrian children into the national education system, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266069

- 26 Syria Crisis: Education Fact Sheet, http://www.oosci-mena.org/uploads/1/wysiwyg/Syria_Crisis_5_Year_Education_Fact_Sheet_English_FINAL.pdf

- 27 Turkey Education Sector, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/64599